Why environmental regulations are on the chopping block (Part Two)

What monied interests do when they can't change the law

One could think the last 60 to 70 years has been an era of progress for black people and other minorities. In the fifties and sixties, court decisions banned racial segregation; Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. More black people went to college and entered professional careers. Barack Obama, a black man, was elected president in 2008.

And yet, as the ink was barely dry on the Brown v. Board of Education decision that outlawed school segregation in 1954, a lot of white people were plotting to keep white kids in one school and black kids in another. In Virginia in the 1950s, they came up with the idea of school vouchers, which allowed white parents to send their children to segregated “academies,” a scheme that continues today, even at the federal level. This desire to keep schools segregated helped to fuel the 1980 presidential run of Ronald Reagan. Today’s headlines remind us that we haven’t seen the end, as the Supreme Court has rolled back Affirmative Action and Ron DeSantis creates what I like to think of as “Jim Crow of the mind” legislation in Florida that teaches kids that antebellum slaves benefitted from their forced servitude.

The same can be said of environmental progress. Things looked great in the early seventies, with the passage of the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, and the Endangered Species Act. Progress was palpable. Dense, choking smog left Los Angeles. Almost completely extirpated, the brown pelican and bald eagle once again soared over coastlines and forests. The Cuyahoga River didn’t catch on fire anymore.

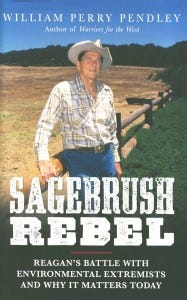

Yet, just as streams started to run clean and imperiled species rebounded from extinction, there were forces pushing to undo the environmental safeguards of the 1970s. Western ranchers, miners, and loggers as a whole did not like the new environmental regulations of the 1970s, but it was the passage of the Federal Land Policy Management Act of 1976 that drew their most bitter ire. Until then, the extractive industries had enjoyed an open door policy to federally controlled lands that allowed easy permitting of mining and logging, as well as ranchers having generous grazing rights. Royalties and fees were low or nonexistent. A product of the Carter Administration, whom many westerners instinctively loathed, the new legislation emphasized a degree of preservation.1 In response, the ranchers, loggers and miners started what became known as the Sagebrush Rebellion.

Like the “states rights” campaigns of segregationists, the Sagebrush Rebellion sought more local control, which would undercut the Land Policy Management Act.2 The rebellion ran the gamut from county officials and state representatives all the way up to state representatives and senators in Washington, DC. At the time, the polarization that characterizes our politics today was still a long way in the future. GOP politicians, such as the very conservative Senator Orrin Hatch of Utah joined Democrats, such as Nevada Senator Jim Santini, in legislatively advancing state control of federal lands in the West.

The rebellion had an uphill battle. The outpouring of support for the environment with the celebration of the first Earth Day in 1970 was a recent memory and still strong. Large cities were seeing bluer skies. Preventing factories from dumping industrial waste into rivers and lakes was still thought of as a good thing. While there was broad support for environmental protections, the Sagebrush Rebellion was restricted to the West, comprising states with small populations. In 1980, the population of the entire state of Nevada was 810,000, New Mexico 1,310,000, Wyoming 474,000.

Although portrayed as grassroots, the rebellion was one of monied interests and wealth. Those voicing their grievances were a minority of large land owners and the operators of mines and lumber companies, not average folks. It was called a rebellion, but there weren’t crowds chanting slogans in the streets.

Without broad support, the rebellion stalled. Legislation to weaken environmental regulation or grant states more control over federal lands went nowhere. But those wealthy rebellious folks soon learned that they could get what they wanted without changing the law.

Once again we return to Ronald Reagan, who appointed James Watt as Interior Secretary,3 and Anne Gorsuch as head of the EPA. It is difficult to describe how radical Watt was. Previous administrators of federal agencies had been quiet office holders, more or less executing their duties in a faithful manner. Watt was anything but. As Time Magazine wrote of Watt at the time, “he wrought deep changes mainly without changing laws; his tools were budgetary finesse, regulatory manipulation and personnel shifts.” He rewrote 93 percent of all surface mining rules and proposed that by the year 2000, all 80 million acres of U.S. wilderness be opened up for drilling and mining. During her time at the EPA, Gorsuch slashed its budget and said the agency would hand over enforcement of environmental laws to the states. She described many environmental laws as unnecessary.4

Not a word of the Clean Water and Air Acts and other environmental laws had been changed, but environmental protections had been seriously curtailed.

Environmentalists were heartened that both Watt and Gorsuch were short-tenured. It was not for his environmental malfeasance that Watt resigned. Rather, he brought scandal upon himself for saying something stupid, anti-Jewish, mysogynistic, and racist all at the same time. It’s hard to believe that anybody could do that, but he did. Gorsuch resigned, disgraced in a political scandal. She had withheld millions of disbursements in Superfund monies directed to California in an effort to hurt the gubernatorial campaign of Democrat Jerry Brown. When Congress investigated the matter, she refused to turn over documents for their inquiry. Congress subsequently found her in contempt, making Gorsuch the first agency director to be so censured by the legislative body.

The resignations did not stem the tide of anti-environmentalism. There were more slashes and cuts through the years. And keep in mind the resignation of Gorsuch left a deep impression on her son, a 15-year-old Neil Gorsuch.

X

GLADWIN H. "Stakes are High in the 'Sagebrush Rebellion'." New York Times (1923-), Sep 02 1979, p. 1.

"Around the Nation: Western Delegates Seek State Control of Lands Rehnquist Orders Nevada to Delay Killer's Execution High School Students Join Busing Plan in Columbus." New York Times (1923-), Sep 08 1979, p. 10.

WILLIAM E SCHMIDT, Special to the New,York Times. "Watt Pleasing the West’s Governors." New York Times, Late Edition (East Coast) ed., Sep 13 1981

LEO H. CARNEY. "New E.P.A. Official: Sees no Rollbacks." New York Times (1923-), Jun 21, 1981

This is a helpful reminder of how much harm the reactionaries can do--and, sadly, are still attempting to do--to environmental progress. My latest novel contemplates the results if they win, and the results ain't pretty. Good for you for reminding us of this history.