Ocean acidification passes planetary boundary

The CO2 we emit to the atmosphere also affects the world's oceans

Before diving into this week’s topic, I’d like to thank

, who publishes Global Nature Beat, for alerting me to this topic. Every week Mike puts together an exhaustive summary of environmental news, as well as job listings for environmental journalists and other resources. If you are unfamiliar with Global Nature Beat, check it out. It’s one of the best environmental Substacks.Ocean acidification boundary crossed

According to a paper published on Monday of this week, ocean acidification, a byproduct of increasing atmospheric CO2, may have passed a critical boundary, thus endangering the ecologies of all the world’s oceans. This research was supported by European Space Agency, the Natural Environment Research Council, the Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing and Ocean Acidification Programs sponsored by NOAA, and the Slovene Research Agency. The paper was published in the journal Global Change Biology.

About 30 percent of the CO2 we release with our smokestacks, tailpipes, and other industrial burning of fossil fuels is absorbed by the world’s oceans. The molecules of CO2 don’t remain as a diffused gas but interact with water molecules, ultimately producing carbonic acid. So as we continue to build up carbon dioxide in the atmosphere we are also making the oceans of the world more and more acidic, a process called ocean acidification.

This chemical interaction between atmospheric CO2 and the world’s bodies of water has always occurred. It also happens in raindrops and makes rainwater is ever so slightly acidic. But since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s, anthropogenic carbon dioxide has changed the pH of the oceans. From 1950 to 2020 the Ph of the oceans fell from approximately 8.15 to 8.05. (Neutral pH is 7.0; the oceans are naturally slightly alkaline.)

First proposed in 2009, planetary boundaries are just that: boundaries on global processes affected by human activity. If these limits are crossed, permanent, unacceptable environmental change becomes the reality of our planet. The research team used updated computer modeling and concluded that the planetary boundary for ocean acidification was passed in the year 2020.

A group of 28 globally prominent scientists led by former Stockholm Resilience Center director Johan Rockström derived the boundaries. You might argue that these boundaries are just guesses—and they are. But they do offer an informed framework. Besides ocean acidification, the boundaries include climate change, degradation of freshwater systems, and a half-dozen other global processes. In 2023, it was estimated that six of the nine planetary boundaries had already been crossed.

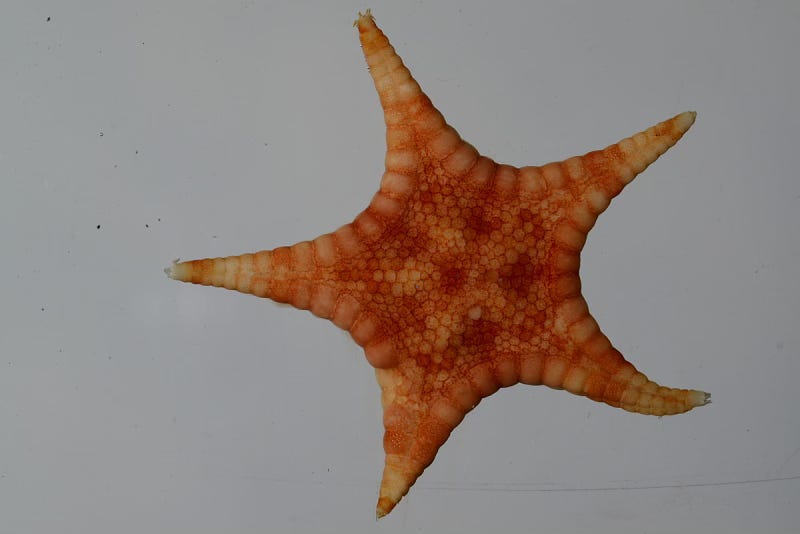

Ocean acidification is particularly problematic for creatures such as oysters, clams, and sea urchins. The increased acidity makes it difficult for them to form their shells. Corals also have a harder time forming their structures. It was thought that fish would be more resilient to more acidic waters, but scientists have found that some fish, such as skates, have a hard time forming cartilage and skeletons when their environment is more acidic. Other functions, such as reproduction, can also be affected by the change in the oceans’ pH levels.

Because of ocean currents, temperature variations, and other factors, the level of ocean acidification varies throughout the world. Acidity in tropical regions can be twice that of polar regions. Recent research has also found that acidification is spreading to deeper waters. The authors of this most recent paper extended their inquiry to the subsurface ocean and found that up to 60 percent of the global subsurface waters—down to 600 feet—had crossed the planetary boundary, compared to around 40 percent of the surface oceans.

Scientists have been warning about the threat ocean acidification regarding seafood production. Many of the sources I relied on for this post still speak of this threat as something that may occur in the future, but the lower pH of the oceans has already affected local seafood production in San Diego, where I live.

With operations in Carlsbad’s Agua Hedionda Lagoon, Carlsbad Aquafarm grows clams from “seed,” almost microscopic clam offspring, which they ship in from the Pacific Northwest. In 2007 the production of clam seed was almost completely decimated because of ocean acidification, with a failure rate of 90 to 95 percent, forcing the seafood farm to change operations and produce its own seed.

The aqua farm found a work-around for the effects that acidification posed to its business, but currently there are no large-scale efforts to counteract what we are doing to our oceans. A few solutions being tossed around in scientific and policy circles include the high-tech direct removal of CO2 from the water. Others have proposed cultivating large amounts of phytoplankton or seaweed, both of which sequester lots of CO2.

Have you noticed changes in the oceans that may be due to acidification? Is it harder to find and catch fish, for example? What have you observed about coral reefs and crusty creatures like sea stars? Share your findings and thoughts in a comment.

Dispatch business

Thanks so much to all who participated in last week’s poll. I asked if folks wanted The Green Dispatch coming to their inboxes more than once a week. The response was overwhelming. Almost 90 percent said that once a week was just fine. This means a sacrifice in timeliness, with fewer posts about news items, such as last week’s Dispatch on Trump officials promoting fossil fuels in Alaska and more posts about developments in the science of the environment.

And another big thanks to all of those who occasionally click my tip jar. It helps to keep this Substack going.

If you liked reading about the world’s oceans, you may want to check out At Every Depth, a book on our ever-changing relationship to our oceans.

At Every Depth: Our Growing Knowledge of the Changing Oceans

At Every Depth: Our Growing Knowledge of the Changing Oceans

Research has shown that jellyfish have a higher tolerance of ocean acidification than most other species, which is why the seas are full of jellyfish in my dystopian novel, We Once Were Giants — which of course you were kind enough to review!

You're staring at the crack in the wall and calling it a structural failure of the paint.

Yes, the oceans are changing. The pH is dropping. The chemistry is going haywire. You got that part right. But you've swallowed the official explanation whole, like a pelican swallowing a rotten fish. You attribute it all to CO2, the convenient bogeyman, because that's what the pay-rolled scientists at NOAA and the rest of the alphabet soup agencies tell you to think.

It's a beautiful, elegant, profitable lie.

What about the massive increase in undersea volcanism? The venting of mantle gases and superheated, acidic water directly into the oceans from a thousand fissures we can't even see? This isn't some side effect of industrialization. It's the planet itself coming to a boil. The Earth's magnetic field is weakening, the poles are wandering, and the core is heating up. This is happening across the solar system, but they don't want you looking at that data.

They focus you on CO2 because they can tax it. They can regulate it. They can build a global control grid around it. They can't tax a goddamn geomagnetic excursion.

So you write about clam farms in Carlsbad finding a workaround. That's cute. It's like hearing a man whose house is sliding into the sea is proud he's figured out how to keep his pictures hanging straight on the wall. You are documenting the minutiae of the demolition while completely ignoring the wrecking ball.