Can We Turn Down the Air Conditioning?

Plus White-Nose Syndrome and a Bill For More Conservation Funding

The climate plan for the county of San Diego, which relied to a great degree on buying carbon offsets instead of actually doing something about the County’s greenhouse gases, was found to be out of compliance with CEQA, California’s environmental quality law.

To establish a new plan, the County hosted an online workshop last week. As a resident of the County, I took part. The folks who are putting the County’s climate plan together seemed earnest enough, yet true enthusiasm, as well as imagination, seemed a little thin. As participants, we were asked to fill out online questionnaires. But I got the feeling that, at least in some ways, the whole exercise was simply fulfilling a legal obligation. Public input is required; so the County got its public input.

Like most cities in the U.S., the city of San Diego has a Climate Action Plan, which the City adopted in 2015, and much of the City’s plan seems underwhelming, too. The San Diego plan could be the climate plan for Cleveland, Orlando, or Pittsburgh. Reading through the document, I don’t see how anyone could really feel that this plan was made for San Diego. Here is the section on “Spurring Economic Development”:

Reinvestment in local buildings and infrastructure will provide new opportunities for skilled trades and a variety of professional services as well as increasing San Diego’s global competitiveness in the world economy. The methods and tools include public/private partnerships and hands-on training, providing an opportunity for labor and businesses to work together to build a green economy.

Go on, substitute “Green Bay” or “Toledo” for “San Diego” in that section and you’ll see what I’m talking about. The rest of the plan reads similarly. I’m afraid that this generic view of our climate problem may have kept a lot of folks from seeing all the advantages that we San Diegans have when we are combating global warming on a local level.

I think the plan overlooks the wonderful climate that we enjoy here in San Diego. (And I’m afraid that the County’s plan will make a similar oversight.) Because of the mitigating effect of the Pacific Ocean, coastal San Diego rarely gets very hot or very cold. That is a big, big plus for San Diego’s climate strategy. Despite the Mojave Desert and Death Valley, California as a whole experiences a fairly mild climate, which places us in the lead for lower per capita carbon emissions in the first place.

Things have gotten warmer here, that’s for sure. I know of several San Diego families who are now glad that they installed air conditioning in their homes in the last few years. Ironically, all of them admit they would not have considered this 20 years ago, before we started to have more sweltering days during summer because of global warming.

Before we go much further, I should note that hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), the substances used in air conditioners, are greenhouse gases once they are released into the atmosphere, and they would be a large part of this discussion. But an international agreement was made in 2016 to phase them out. Nonetheless, air conditioning still needs to be addressed in policies intended to keep the planet cool.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, in 2020 space cooling for residential and commercial buildings used 392 billion kilowatt hours of electricity, accounting for about ten percent of all electricity consumed in the U.S. According to the Department of Energy, on average, each home with an air conditioner releases about two tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year; for the country as a whole, that comes out to about 117 million tons of CO2.

I’m not proposing that we simply turn off the AC. But there are a handful of strategies that the City, County, and we as individuals can do to reduce or cut out the AC. Considering that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released this report in 2018 claiming that we have about 12 years (now nine) to get our greenhouse gas act together before things turn really bad, every effort to keep another molecule of CO2 out of the atmosphere should be considered.

Even if we can cool our homes and workplaces without HFCs and with 100 percent renewable energy, that renewable energy may still be diverted from more appropriate uses in San Diego. Phasing out our use of large- and small-scale cooling would one of the most appropriate things the city and county of San Diego could do to keep our planet cool.

Living without air conditioning is conceivable; after all, this modern luxury only really began to gain ground around 65 years ago.1 And it is in fairly recent memory that air conditioning became the ubiquitous comfort that we know it to be. As late as 1993, air conditioning was found in just 68 percent of all U.S. housing. Now 87 percent are air-conditioned.

There has been some movement to return to building structures without air conditioning. The architectural firm Weber Thompson received the rare LEED Platinum Certification for their office building in Seattle in part because the building was designed without air conditioning.

In some cases, air conditioning makes life ridiculous. As the Boston Globe points out, air conditioning allows us to do things that we really don’t want or need to do. Businesses that are air-conditioned are usually supercooled by four to six degrees more than what most folks would consider comfortable, so businesspeople, mostly men, can wear suits in their offices. And what about the ubiquitous space heaters tucked under the desks of administrative staff to keep them warm during their workday?

The great natural air conditioning resource for the county of San Diego is the Pacific Ocean. Ocean currents that originate far north of here flow along our coastline, keeping San Diego County, as well as a lot of California, pretty cool.

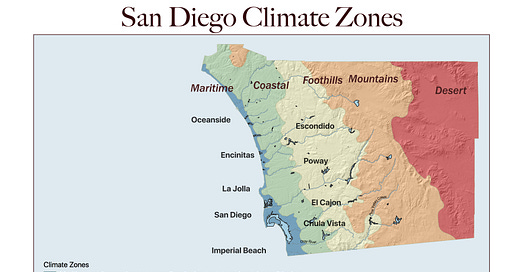

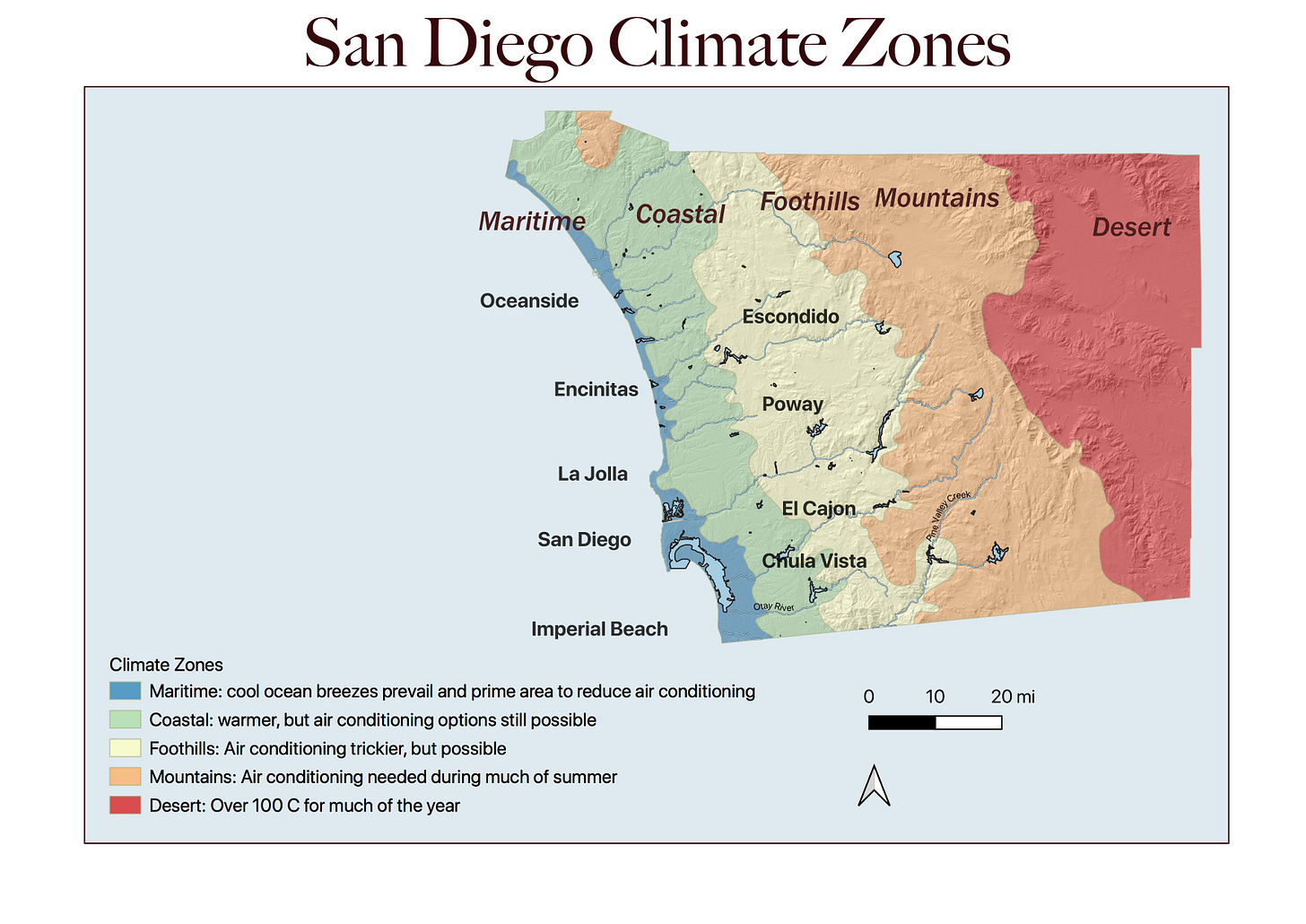

As you can see in the above map of San Diego County, much of the maritime and coastal areas could do without air conditioning, or at least have it as an occasional option. Much of the population lives along the coast already in the cities of Oceanside, Encinitas, La Jolla, San Diego, and Imperial Beach.

San Diego could foster architecture that takes advantage of this natural cooling and become less reliant on air conditioning. The city could establish building codes that require that any of a number of cooling strategies be incorporated into the designs of new homes. For example, most of our prevailing and cooling winds are east-west. Codes could be developed to require new homes to have good east-west ventilation or ventilation that takes advantage of their area’s particular local winds. Codes could also require other cooling structures such as transoms that help to ventilate hot air out of rooms and buildings.

Irving Gill, a contemporary of Frank Lloyd Wright, designed homes and buildings in San Diego at the turn of the 20th century. Many of these were designed for natural heating and cooling. Notably, many Gill homes have overhangs shading their windows. These structures protect the indoors from the hot summer sun yet allow sunlight to warm the indoors in the winter.

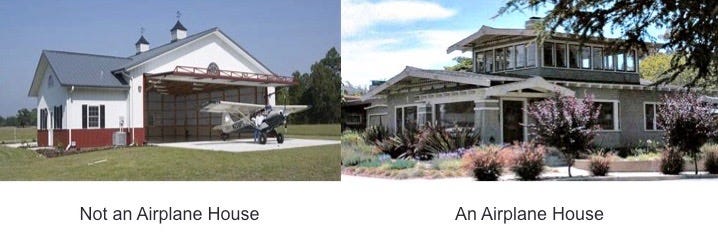

Another architectural style popular in San Diego around 100 years ago was the airplane bungalow. These are houses with a second story, smaller than the footprint of the first, with multiple windows for plenty of natural ventilation. These charming houses are well known for their natural air conditioning.

Other designs have traditionally been used to mitigate the summer heat, such as the use of double-hung windows to take advantage of convection and ventilation by adjusting the top and bottom windows.

The County could require lighter-shaded building exteriors, especially roofs. This not only keeps the individual structure cooler but also helps to reduce the heat island effect that makes urban areas hotter than the surrounding countryside.

The city of San Diego already has plans to increase the tree canopy of the city. Not only do trees make city streets more attractive and livable, they also cool down neighborhoods and urban areas, which reduces our reliance on air conditioning.

Do you have any comments on this? Is living without air conditioning impossible? Will the heat of climate change actually make air conditioning more of a necessity? What of other cities? They may not have ocean breezes, but could other places make air conditioning an option or something to do away with completely?

Other News

White-Nose Syndrome has Killed Over 90 Percent of Three American Bat Species

Almost all of the little brown, northern long-eared, and tri-colored bats in the U.S. were killed off by the white-nose syndrome within a ten-year period. No treatment for the disease has been found, but scientists and conservationists remain hopeful. (U.S. Geological Survey)

A Bill to Increase Funds for Wildlife Recovery

Representatives Debbie Dingell (D-MI) and Jeff Fortenberry (R-NE) reintroduced the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act to the House of Representatives this past week. If passed into law, the legislation would send $1.3 billion to states and territories and $97.5 million to indigenous nations every year to fund conservation efforts. (Audubon)

For more environmental news that doesn’t make the headlines, follow me on Twitter @EcoScripsit.

John Willig. "This Year, with a Million More Americans Adding Climate Control, Air Conditioning is Becoming a Part of Everyday Life." New York Times May 15, 1955.