News of the week

Great news for crayfish and other critters that live in the creeks of Appalachia

After almost seven years of stalling and delays, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service this week designated 446 miles of streams in West Virginia, Kentucky and Virginia as critical habitat for the Big Sandy and Guyandotte River crayfish.

Recounting the legal saga that has resulted in this victory for the crustaceans is a reminder of how arduously individuals and organizations have to fight for even the smallest considerations for the natural environment. The designation of critical habitat comes in response to legal proceedings by the Center for Biological Diversity that go back seven years. The Center originally sued the USFWS in 2015, during the Obama administration, seeking Endangered Species status for the two crayfish. On April 7, 2016 the federal agency listed the Big Sand crayfish as Threatened and the Guyandot River crayfish as Endangered, but did nothing to designate habitat for the two invertebrates.

Listing the crayfish without designating habitat is, well, next to useless. Unless the places where the critters have to live are protected, then they are basically unprotected.

More legal wrangling ensued. The Center sued again in 2018, charging that the USFWS was not properly releasing records on the crayfish, a case which the Center won. Finally, this designation of the critical habitat comes in response to a lawsuit that the Center for Biological Diversity filed back in August of 2021.

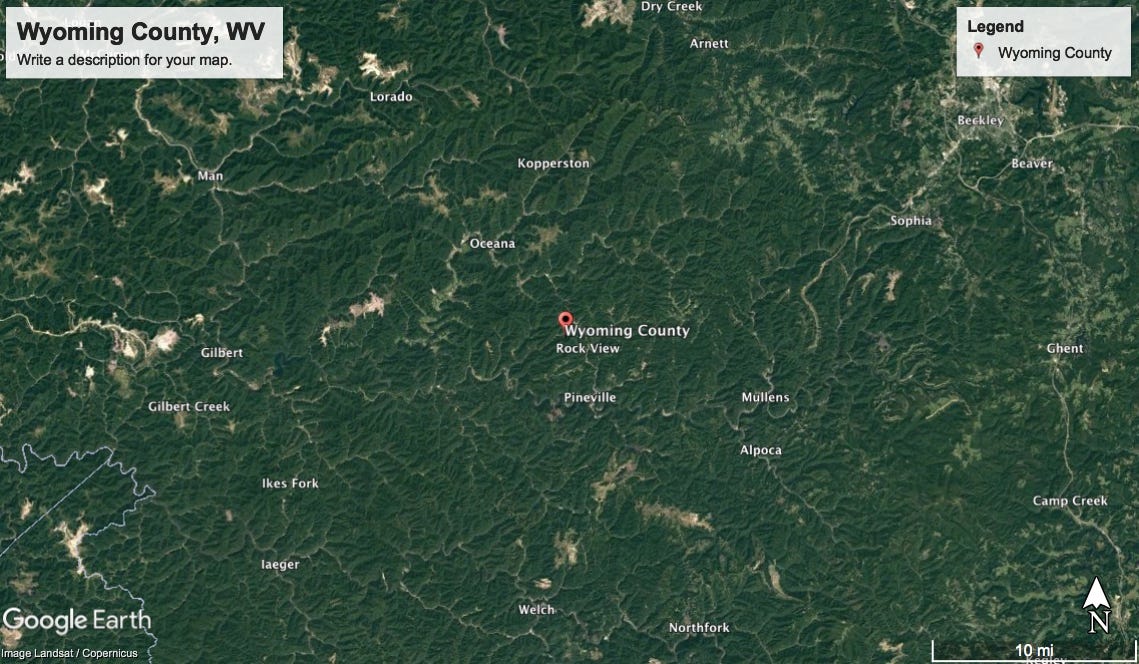

Both crayfish have died out in most of their ranges. The Big Sand Crayfish can be found in only about 60 percent of its historical range. It now lives in only two river networks in southwestern Virginia, southwestern West Virginia, and eastern Kentucky. The loss of habitat is much more severe for the Guyandotte River crayfish, with more than 90 percent being lost. It is now found only in Wyoming County in West Virginia.

Loss of habitat for both crayfish boils down to one thing: coal. Because of coal mining there just aren’t as many streams as there used to be. When mountaintop removal mine operators blow the tops off of mountains, they are allowed to throw the dirt and rocks into adjacent valleys, burying all the land, including streams. As of ten years ago, this practice had buried more than 2,400 miles of Appalachian streams.

Beside the loss of streams, runoff from the mines contains high levels of selenium, sulfur, and other compounds that can poison rivers and streams. As a child growing up in West Virginia, I can remember the acrid smell and the bright yellow stains left on the rocks and stream beds of creeks near the coal mines. Many of these polluted waterways were completely devoid of life. For crayfish to die out, the pollution does not need to get very bad. Though they are hardy creatures, able to tolerate temperature fluctuations and variations in salinity, they are very intolerant of pollution.

Wyoming County, where the Guyandotte River crayfish live, occupies the central area of the Google Earth image below, an area that is about five to seven miles from the central marker for the county. From our sky-high perspective, Wyoming County looks as though it has not suffered as much as other counties when it comes to the mines. It is not a hard guess to see why the the crayfish no longer live in the other streams close by. All the whitish splotches in the arial view are mountaintop removal mines.

The Endangered and Threatened status made it illegal to directly harm the two crayfish. Critical habitat designation makes it more difficult for people to harm the streams where they live. Any federally funded or permitted project, such as coal mining, now needs to consult with the USFWS to ensure that the crayfish habitat is not harmed. A side benefit from this designation is that other creatures that live in the protected streams now enjoy being protected, too.

I am uncertain what this habitat designation might mean for the coal mines in Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia. After more than 40 years of mountaintop removal mining, my guess is that the coalfields are mined out. I don’t know if there is much more coal to be dug out of those hills.

Crayfish are arthropods, the same phylum to which beetles and butterflies belong. They are closely related to lobsters and kinda look like them, too. (One nickname for crayfish is rock lobster.) They grow to about three to six inches in length, have a fused head and thorax, and their eyes are at the ends of stalks. They of course have those big pincers.

As Fred Schnieder and the B-52’s will tell you, it wasn’t a rock, it was a rock lobster. And now it’s a rock lobster with Endangered species listing and critical habitat designation.

For more environmental science and news follow me on Twitter @EcoScripsit.