News of the week

Black rhinos reintroduced to a Zimbabwe park. Looking at wildlife corridors.

Black rhinos reintroduced to Zimbabwean National Park

Black rhinoceroses have been reintroduced to the Gonarezhou National Park in Zimbabwe. A population derived from three other areas within the country was relocated and released this month. Rhinos had been extirpated from the park for the last 30 years.

Occupying almost 2,000 square miles of wilderness, Gonarezhou is Zimbabwe’s second largest national park. Originally established as a game reserve, the expanse of woodlands and brush lands was declared a national park in 1975. Bordering Mozambique, the park constitutes part of the Greater Limpopo Transfrontier Park, which was established in 2002. Occupying portions of Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, the Transfrontier Park conserves 13,500 square miles, an area slightly larger than the state of Maryland.

Weighing between 1,750 to a little over 3,000 pounds, adult black rhinoceroses stand about five feet tall at the shoulder and are about 11 to 12 feet in length. Their cousins, the white rhinos, are a little bit bigger.

Their double (sometimes triple) horns are used for digging up roots, breaking branches, defense, and looking badass. Black rhinoceroses are solitary, except when breeding or raising young. As herbivores, most of their diet consists of leaves, shoots, branches, and fruit.

The black rhinoceros was hunted nearly to extinction in the 20th century, with numbers of the species declining to less than 2,500 by 1995. Still considered critically endangered, the black rhino has made a dramatic comeback, more than doubling its numbers to around 5,600 today. Poaching for the animals’ horns remains a threat to their recovery.

The reintroduction of the rhinos was performed under the auspice of the Gonarezhou Conservation Trust, which manages the Gonarezhou National Park and is a partnership between the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority and the Frankfurt Zoological Society. (Frankfurt Zoological Society)

Wildlife Corridors

A new report from Environment America examines and promotes the effectiveness of wildlife corridors. Wildlife is just that, wild. Critters need to roam for mating, to find food, and to perform ecological functions, such as seed dispersal. Animals have always naturally done this, but now that we have highways, dams, and other things in their way, animals need to find ways around our obstacles.

A wildlife corridor is any route that an animal needs to crawl, swim, or fly to complete its life cycle. They can be as small as a stretch of river or can span more than a continent. When folks talk about making wildlife corridors, we’re talking about making or finding ways for animals to use their travel routes without the interference of the built environment. For the remainder of this newsletter, we’ll be talking about the human made or designated wildlife corridors.

Wildlife corridors can take many forms. A corridor can be a single, small-scale project, such as a highway crossing, or it can encompass a series of large-scale networks of refuges that serve as resting spots for migrating birds.

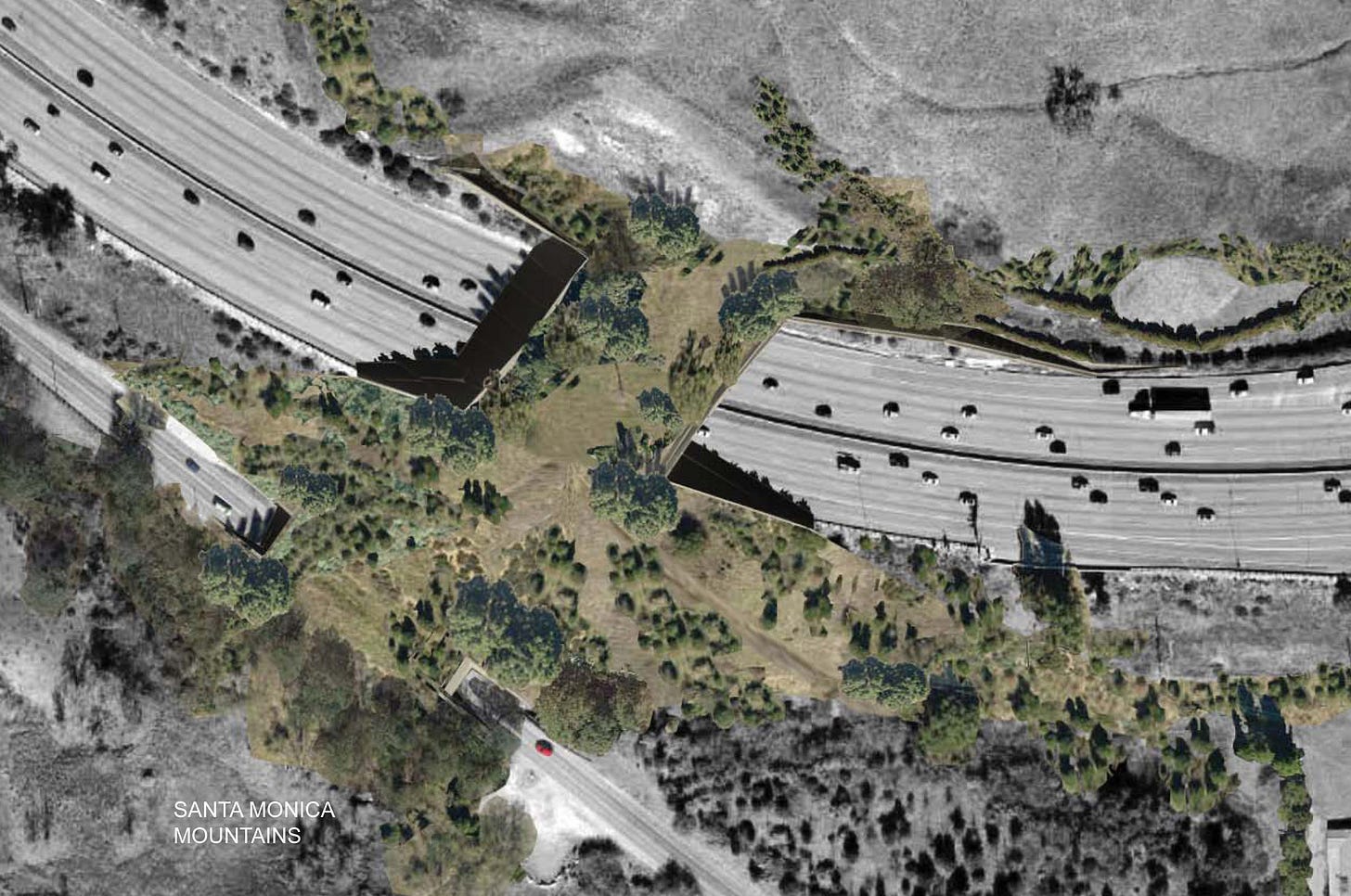

A single corridor across a freeway

In 2019, my wife and I visited friends in Ventura. On the way, we drove along Highway 101, which is more commonly called the Ventura Freeway. Often eight lanes or more, the freeway presents an impenetrable barrier for a lot of critters, including mountain lions that live in the Santa Monica Mountains. Hemmed in by development, the Santa Monica mountain lions will suffer from inbreeding in just a few generations if they are unable to mate with lions from outside the mountains.

To remedy this, a consortium of environmental organizations and government agencies is planning for the construction of a 165-foot wide wildlife corridor across Highway 101 at Liberty Canyon. The corridor, a bridge, will be covered in soil and planted with native plants, giving a seamless sense of habitat across the freeway. It is hoped that the mountain lions will find it hospitable for crossing to the Simi Hills to the north.

A corridor from a simple fence redesign

When winter comes along in Wyoming, elk migrate from the high country to overwinter at the National Elk Refuge. Much of the land is fenced, but sections of lowered fencing, known as elk jumps, allow the elks to traverse the fencing, but also limit their ability to leap out near highways, where they could be struck by automobiles.

A wildlife corridor on a grand scale

Eastern Kentucky is plagued by poverty and an especially destructive type of coal mining called mountaintop removal. There is nonetheless a great deal of wilderness and wildlife. The mesophytic forest that blankets the Appalachian Mountains through Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia is one of the most biologically diverse temperate regions in the world. More than 30 canopy tree species might occupy a single forest site, with a rich understory of fungi, ferns, and shrubs that support insects, amphibians, and songbirds.

The Pine Mountains Wildlands Corridor traverses 125 miles through eastern Kentucky and connects habitat for bears and other creatures from Tennessee to Virginia. The corridor is part of a larger conservation system known as the Eastern Wildway, which is a new vision of connected or nearly connected wilderness, from the northern terminus of the Appalachian Mountains in Maine all the way down to southern Florida.

Recommendations

Environment America offers recommendations for local, state, and the federal government to create or enhance wildlife corridors. As in the case of the wildlife bridge across Highway 101, most efforts for corridors are post hoc. The environmental organization recommends that wildlife corridors become part of the initial design when any highway or other large construction project is commenced. (Environment America)

For more environmental news follow me on Twitter @EcoScripsit.