In the last six to seven years, a large number of states and some European countries have criminalized protest of all sorts, and many of them target environmental protests.

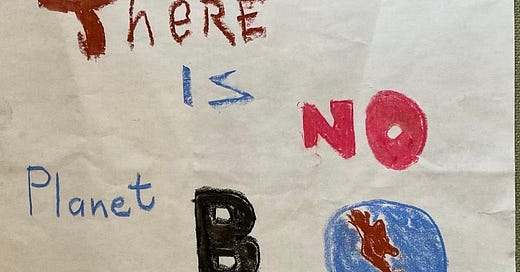

Protest is ingrained into the environmental movement. In the typical scenario, a community learns of a corporation dumping toxic waste into local waterways. People demonstrate, contact their political representatives, and generally raise a ruckus until something is done. People do similar things when they feel the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is dragging its feet on listing endangered species. When forests are threatened with logging, protesters have climbed up tall trees and stayed there. At least one, Julia Butterfly Hill, managed to stay aloft in the branches of a tree for over two years.

Having grown up in the 1960s, protest was as much a part of my life as the Sears catalogue and rotary telephones. Reverend Martin Luther King organized the March on Washington in 1963, with other civil rights protests following. By the end of the decade, antiwar protests were common on college campuses and cities. In the early seventies, the women’s movement often took to the streets.

We can think of the age of protest as having its heyday and virtually disappearing from our lives, but real protest continues. The Women’s March in January 2017 drew an estimate 4.6 million individuals to demonstrations and other events throughout the United States and is possibly the largest single-day protest in our history. Millions of others joined the protest all over the world. Both the Mountain Valley Pipeline, an oil pipeline through Virginia and West Virginia, and the Keystone Pipeline, connecting Canadian tar sands oil with oil terminals in Texas and Illinois, have received a great deal of pushback from communities and environmentalists.

The following video depicts tree sitters protesting the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

If a protest is unpermitted or if protesters wind up disrupting traffic or otherwise engage in tomfoolery (violence, like throwing bricks or assaulting police, is another, more serious matter), police usually warn folks to disperse before making arrests. When protesters are arrested, charges usually amount to failure to disperse or unlawful assembly. Where I live, California, treats both as misdemeanors, with the greatest penalties being fines up to $1,000 and six months in jail. Penalties have been similar throughout the United States.

Since 2017, however, legislators in 45 states have proposed almost 300 bills to restrict or highly punish protest. Some of these are in response to the protests prompted by the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in 2020. Others are seeking to weaken the efforts of environmental organizations, community groups, and individuals protesting oil pipelines and fossil fuel companies. At least 21 states have enacted legislation that makes protest more legally hazardous, imposing harsher penalties on protest activities. Of these 21 states, 18 have made laws that target pipeline or fossil fuel protesters.

For example, in Wisconsin, trespassing on the property of any "company that operates a gas, oil, petroleum, refined petroleum product, renewable fuel, water, or chemical generation, storage, transportation, or delivery system" is now a felony punishable by up to six years in prison. Similar actions in Tennessee can also get you six years as well. Mind you, trespassing just about anyplace else remains a misdemeanor.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Green Dispatch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.