Malaria: cuts to USAID spell trouble, yet new research promises hope

Many predict a higher death toll from the water-borne disease due to Trump's slashing of USAID

This is the height of malaria season in Africa, which coincides with the rainy season in much of the continent. Africa bears the brunt of the water-borne disease. Of the almost 600,000 people who annually succumb to malaria worldwide, 95 percent of those deaths occur in Africa. The countries suffering the most from the disease are Nigeria, Congo, and Uganda. In 2023, Uganda, a country of 49 million, had 12.6 million cases of malaria, around a quarter of the population. Conflict in Congo’s east, which has been ongoing since 1996, complicates efforts to fight malaria in that country.

Across the globe, the disease afflicts children the hardest. Children under five comprise 76 percent of malaria cases.

This year, African health officials are expressing grave concern, as Donald Trump and Elon Musk have terminated 90 percent of USAID’s foreign aid, which has funded and supported anti-malarial efforts. Until now, the U.S. has funded most malarial mitigation in Africa. The cuts come at a time when a shortfall already exists. Global anti-malaria funding in 2023 stood at $4 billion, less than half of the $8.3 billion target.

Malaria No More, a nonprofit that seeks to eradicate malaria, claimed that just one year of disruption to malaria control would result in 15 million more cases and over 100,000 additional malaria deaths worldwide.

Robert Redfield, who controversially headed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention during Trump’s first term, defends Trump in an opinion piece for the industry front organization The Heritage Foundation. Redfield says despite Trump’s slashing of staff and funding for the CDC, USAID, and other federal government health agencies, Trump and his administration are maintaining the government’s malaria initiatives. But others, writing in the more mainstream press, claim that funding for malaria efforts are in Trump’s crosshairs. The warnings of others are far from sanguine and are actually quite dire.

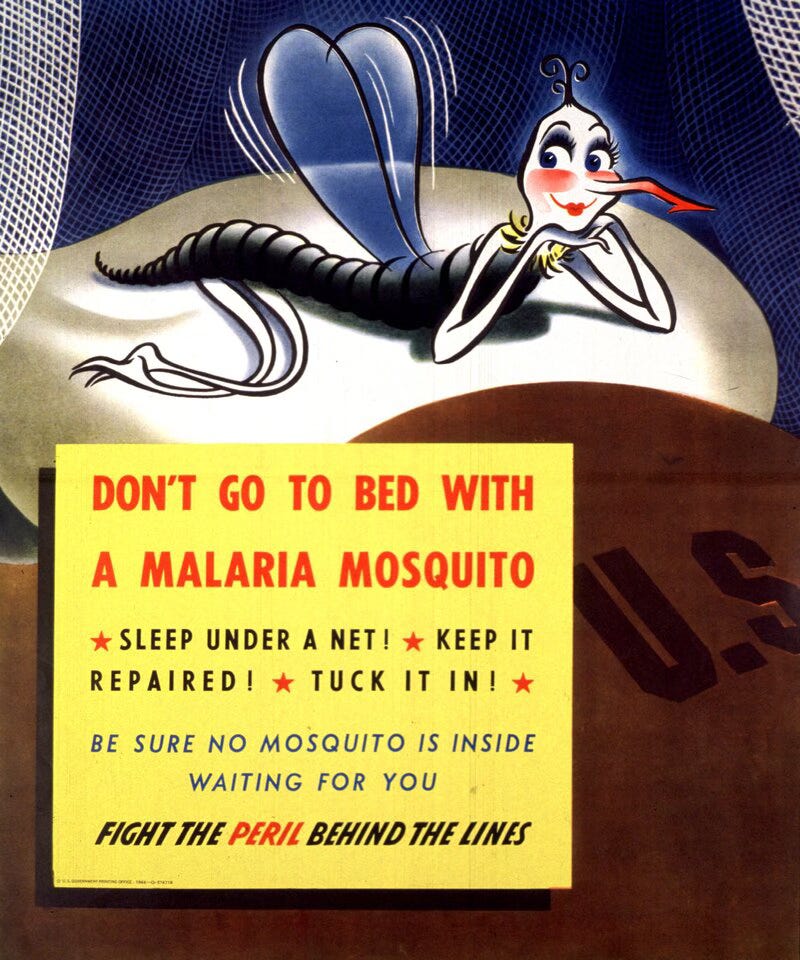

Malaria is caused by any one of five parasitic microorganism species that are transmitted by female Anopheles mosquitos. (It’s the females that bite and suck blood. Males visit flowers for nectar.) Most efforts to fight malaria concentrate on controlling or protecting people from mosquitos. These include draining water bodies where mosquito larvae live, the use of insecticides, and employing bed netting that shields against nighttime mosquito bites. (Most mosquito species are active at night.) Malaria symptoms resemble the flu, with chills and fever. Left untreated, folks can die of malaria.

While the cuts to USAID are shocking, other challenges include drug and insecticide resistance and invasive mosquito species that further spread the disease. In many parts of Africa, language barriers persist. Many people don’t learn how to protect themselves because malaria education is not delivered in their local language.

Another factor exacerbating malaria is global heating. Cooler regions of Uganda that had been free of malaria because their climate had been too cool for malaria-transmitting mosquitos are now experiencing rising temperatures as well as a rise in cases of malaria. Scientists and health experts expect malaria to spread in other parts of the world due to climate change.

New research

New research on the salivary glands of female mosquitos, who transmit the disease with their blood-sucking bites, go through a circadian rhythm, waxing and waning through the day. It is hoped that this understanding can lead to new ways to fight malaria and other water-borne diseases.

Insecticides—including DDT, which is still used in many countries—have been used to control mosquito populations. Another strategy is for folks to use anti-parasitic medications, such as ivermectin (yes, that ivermectin). When mosquitoes consume blood containing ivermectin, the bugs’ lives are shortened. Though considered the gold standard of malaria prevention, the drug is environmentally toxic.

In a study published in Science Translational Medicine, researchers found that when subjects take Orfadin (nitisinone), a drug that has traditionally been used to treat certain genetic diseases that affect blood, it killed mosquitos who bite them. Apparently, Orfadin makes the blood indigestible for the insects. Further, the researchers found that Orfadin lasted longer than ivermectin in bloodstreams. It also killed mosquitos more quickly and killed mosquitos that had developed resistance to other insecticides.

In Niger, researchers looked at data on children aged six months to five years and found that household income played a significant role in the likelihood of children being afflicted with malaria. Children from low-income and middle-income homes were 50% and 63.7% more likely to have malaria, respectively, compared to children from high-income households.

Education played a part as well. Children born to mothers with little to no education were more than twice as likely to get malaria than their better-off peers. City children were almost 70 percent less likely to suffer from malaria than children in rural areas. Explaining at least part of their results, the scientists point to previous research that found better educated individuals were more likely to use insecticide-treated mosquito nets. The results were published in BMC Public Health in March. Other research also published last month in BMC Public Health, supports the prophylactic capabilities of bed nets in malarial prone areas.

In the U.S.

I had known that malaria had been a scourge in the United States in the 19th Century, but had not known that it was still common, even as far north as Cleveland, into the 20th century. And it was news to me that malaria was not eradicated in this country until 1951. Large-scale use of insecticides like DDT, the use of screens, draining wetlands, and other measures led to the elimination of the disease here.

Several thousand individuals come down with malaria in the U.S. every year. These are all travelers who have spent time in South America or Southern Africa and brought the disease back with them. In the last few years, however, isolated cases of homegrown malaria have emerged. Last year, five cases of domestic malaria—four in Florida, one in Texas—were reported.

Do you live in a country where malaria occurs? Have you ever had it? Please share your thoughts by clicking the “Leave a comment” button.

Anopheles Trumpii is the global scourge, now.

Look up mosquito nets & their effectiveness. In addition, when contracting the horrid disease, there are some good Nobel prize winning remedies & other—none of which includes a vaccine.

Also look up GM mozzies that have been unleashed in America & around the world without oversight. In addition, “flying syringes” —arming mosquitoes with various goodies. Place your focus there rather than aid to other countries?