In touch: salt marsh bird's-beak

The very rare and endangered marsh plant that I once (gasp!) killed

Salt marsh bird’s-beak is beautiful. The recent photo below does not do it justice.

I’m not a gifted photographer, not even a sort of good one. But even under the best circumstances, and with the best camera, it is difficult to capture the allure and charm of this marsh plant. In full bloom, the flowers subtly transition from green to lavender to purple and white. In the sunshine the blooms shimmer with iridescence.

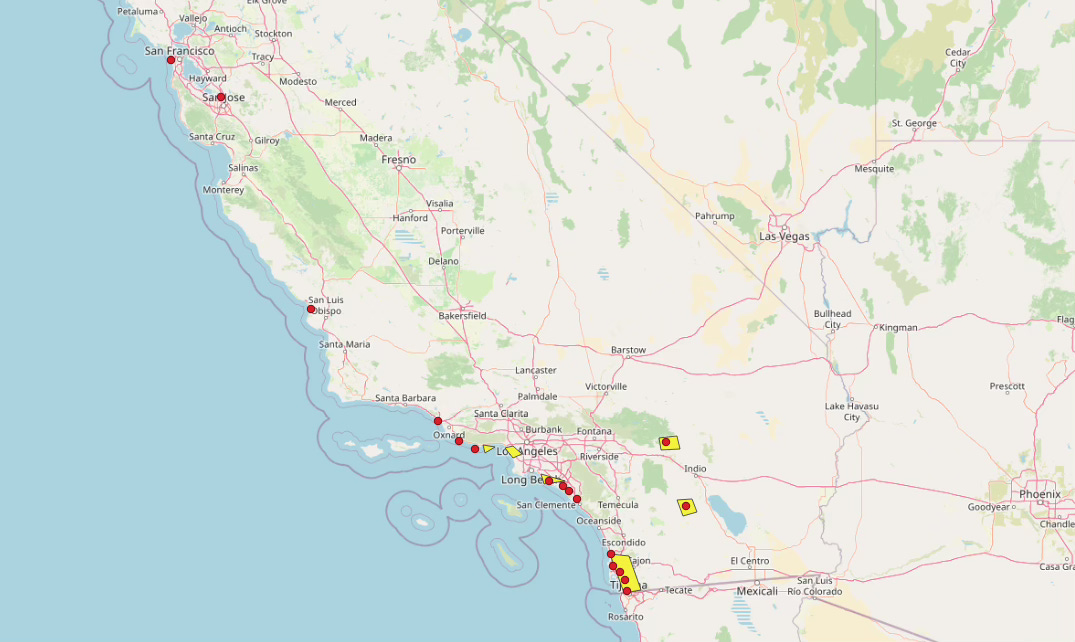

The bird’s-beak is blooming now, making a visit to the estuary of the San Diego River, one of the few places this plant grows, extra special. Salt marsh bird’s beak grows in only a few places in Southern California, mostly along the coast and in northern Baja California, Mexico.

Both the state of California and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service list salt marsh bird’s-beak as endangered. The California Native Plant Society ranks the plant as 1B.2, meaning it is rare, threatened, or endangered in California and elsewhere.

The annual plants are hemiparasititic; although they possess chlorophyl, the plants attach themselves to other marsh plants, usually marsh grasses and pickleweed, and pull some of their nourishment from these plants.

The plant is an Orobanchaceae or Broomrape, a family of flowering plants known to be parasitic, most of which are common to Africa and Madagascar. Scientifically, the plant had been classified as Cordylanthus maritimus ssp. maritimus, but genetic research has revealed the plant to be a different genus of broomrape, Chloropyron, subsequently given the new scientific name Chloropyron maritimum ssp. maritimum. There are two other subspecies of bird’s-beak; all of them are rare and endangered.

As you can see from the map above, the populations of salt marsh bird’s-beak are small, spread out, and can be isolated, leading to genetic isolation, which in the human world is the equivalent of marrying your cousin. This leads to what is called “genetic bottlenecking” and, like the inbred royalty of Europe, can lead to problems of health and reproduction.

Other threats include invasive species, particularly Old World grasses. We are also encroaching on the plant’s habitat and altering coastal hydrology. Sea level rise threatens the plant’s habitat, too.

I recently posted about a paper that colleagues and I got published in a scientific journal. We described several methods of removing an invasive plant from our estuaries here in Southern California. At the time the scientific work commenced, over ten years ago, I knew next to nothing about the estuary plants and could identify only a handful of them. That was when I first became familiar with salt marsh bird’s-beak. Curiously, the invasive plant we were concerned about, nonnative sea lavender, didn’t seem to bother the bird’s-beak. Whole areas had been taken over by the sea lavender, but the bird’s-beak still grew among them just fine.

Testing the removal methods for the invasives meant removing some of the bird’s-beak. It was only a small area, a few square feet, but it was the first time, and actually the only time, that I knowingly took the life of an endangered plant. I felt really weird about doing that. I remember squinting and closing my eyes as I struck a garden hoe around the bird’s-beak, pretending on some level that if I didn’t see the bird’s-beak fall under the garden tool, then it wasn’t happening. This project was reviewed and approved by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Even still, I had a feeling of making a great transgression that day.

As I said, I felt kinda weird, but our efforts were in favor of helping the bird’s-beak and other native plants in the long run. Since the time of our experiment, a recent restoration project has returned much of the estuary to a native status. I’m happy to report from my recent visit to the estuary, the bird’s-beak is thriving there.

There are still folks who let their dogs wander off leash around the estuary. The dogs dig holes and romp around, which disturbs the habitat. There really should be some signage letting folks know that the habitat has been restored and includes at least one endangered species.

This is the 12th in the “In Touch” series for The Green Dispatch: a dozen plants I have surveyed, gardened with, or otherwise been involved with in some way. Although I am not as intimately familiar other rare and endangered species native to southern California, I do have some understanding about them. Would you like to read about these other species? Please let me know in the comments.

Until the public understands the importance of endangered flora & fauna, we are faced with losing so much. But, with government being sometimes as ignorant (or worse) as the general public, we have little hope of saving those endangered species.