Today, The Green Dispatch starts a new series: In Touch. With these Dispatches I want to explain my work or relationship with a plant or animal that deserves recognition, either because it is rare or endangered or because it is significant, such as being a keystone species.

Gardening with estuary seablite

I squeeze the pot in my hands, the earth of the rootball giving way as I rotate and push on the sides. Turned upside down, the plant and rootball are easily released from the pot. I tease out the roots of the rootball, the ones that have swirled up against the sides of the pot, and place the rootball into the hole I’ve just dug. I gather some loose dirt to fill in the hole, making sure that I leave a little moat around the plant to direct water to the roots.

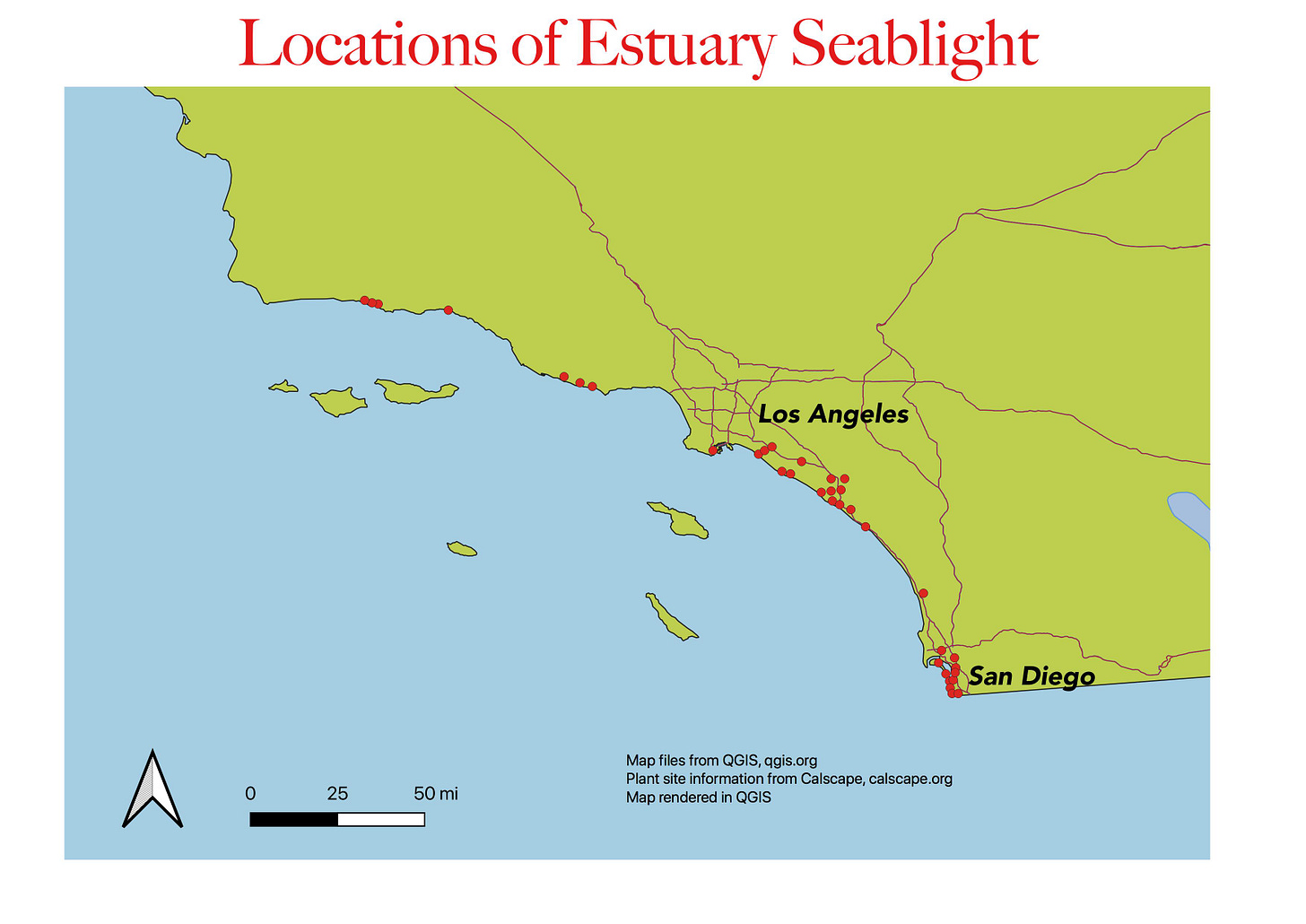

I’ve just planted estuary seablite (Suaeda esteroa), a very rare plant that only grows in estuaries and salt marshes along the coast of southern California and northern Baja, Mexico, so rare that the California Native Plant Society considers estuary seablite to fall under the protection of the California Endangered Species Act. The map below displays the relatively few places that this succulent can be found in California. (I have no information on its location in Baja.)

Planting the seablite is fairly mundane, like planting any other plant. Dig a hole and put the plant in it. But it’s also a little odd and slightly thrilling, like finding out that the person in front of you in line for fish tacos is George Clooney or Sarah Jessica Parker. And I was able to buy this plant at a nursery, with it costing no more than any other plant, even though it is rare and endangered. You would think that I would have had to sign a waver or recite something along the lines of a loyalty oath “I hereby give my assurance to the state of California that, to the best of my abilities, I will properly plant, weed, and water this precious plant, and do all I can to ensure its safety and survival, so help me God.” Something like that. But I just picked up the seablite, along with all the other plants I ordered, and tossed them all in my work truck.

When I was a child, watching nature shows like Wild Kingdom or the occasional National Geographic special, I got the impression that endangered and rare species were exotic, like cheetahs on the savannas of Africa or some small critters that live only in the tundra of northern Saskatchewan. If I wanted to see one of these creatures, I would see it in a zoo or need to travel to the ends of the earth and search through its native habitat. I never thought that I would ever wind up in close contact with any endangered species, let alone plant one as part of my job.

As many of you already know, a couple days a week I work as a gardener at a very small zoo and aquarium on a very small island that skirts an estuary of the San Diego Bay. Among the attractions of southern California—SeaWorld, Disneyland, the San Diego Zoo, etc.—the zoo where I work is unique in that all of our landscaping is done with plants native to the area.* Today, we are replanting in our shorebird exhibit, after much of the exhibit was refurbished.

Recently found to be a separate species

Estuary seablite was differentiated as a separate species from California seablite (Suaeda californica) only about 30 years ago in 1983. In the coastal wetlands of San Diego County I’ve found estuary seablite growing among the more common pickleweed (Salicornia pacifica), which it can sometimes resemble. (Both species are members of the Goosefoot family.)

Like other succulents, the stems of estuary seablite are smooth and fleshy. Coming across seablite in the wild, it generally doesn’t grow much higher than about a foot, but I have seen it in some places growing twice as tall. Depending on the time of year, as in the summer when tides are shallower and there is less water flowing in southern California rivers, seablite can go deciduous. Some of the times that I’ve been able to spot the seablite has been when I’ve found dodder, a parasitic member of the morning glory family that resembles dried straw, growing on it, as you can see in the following photo.

It’s probable that estuary seablite was never a very common plant, as it only lives in coastal wetlands, and only sporadically within that environment. We’ve most likely made the plant even more rare by turning its habitat into marinas and beachfront property. Sea level rise threatens the seablite, the more rapidly it occurs the more at risk this plant is. Even still, the state of California, let alone the federal Fish and Wildlife Service, has not listed estuary seablite as Threatened or Endangered.

For more environmental science and news follow me on Twitter @EcoScripsit.

If you work with an endangered or otherwise significant species and would like to contribute to this series, contact me through the comments. Your work could be restoration, research, reporting, fighting an invasive, or just about any other work with a species.

*This is a big deal, as I will explain in future Green Dispatch publications.

I liked "Species Spotlight"