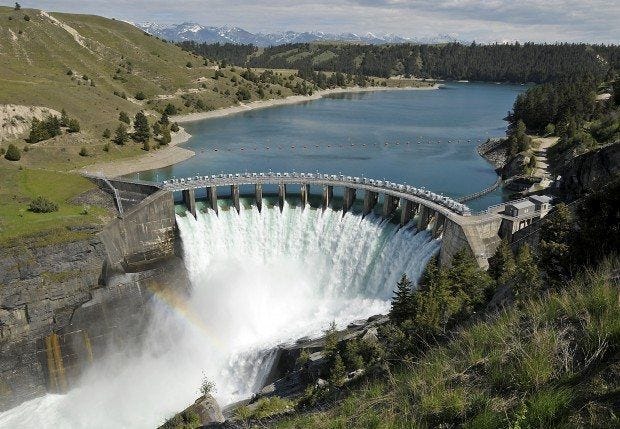

Dams

They Are Often Big, Often Beautiful, Almost Always Useful, But There Are Costs

Dams are a technology that predate humans. Beavers have been building dams ever since they evolved in North America and dispersed to Asia and Europe more than 33 millions years ago. It took humans quite some time after that to start building dams. The first known dam built by people is the Jawa Dam, built by the Mesopotamians in the fourth century BC.

The Romans built lots of dams. And as it would be with Roman engineering, most of their dams were built really well, so well that a number of them, such as the Cornalvo Dam in Spain, are still in use today.

Ever since I was a small child, I’ve been fascinated by dams. I loved their sleek profiles that lay across river channels. And I loved to behold the churning power of the water released at their bases. Some of them are quite beautiful. If you ever have a chance to see the Hoover Dam, it’s art deco stylings turn the structure into a work of art.

Dams create lakes, giving folks a chance to go fishing, swimming, or boating. Hydroelectric power is not entirely carbon neutral, but hydroelectric power stations don’t have big smokestacks spewing soot and ash. Almost seven percent of U.S. electricity comes from hydroelectric power.

But dams can have bad effects on river ecologies, mostly by blocking organisms that need to swim a river or stream to spawn or escape predators. As the surface area of the resulting lake behind a dam is greater than that of a river, the temperature of the water can be raised. This can harm fish and other aquatic organisms.

Dams also lose water. That warmer water in the lake evaporates quicker than water in a river. Desert environments can make this even worse. It’s been estimated that Lake Mead loses as much as 350 billion gallons of water a year. (That is more water than San Diego County uses in a year and a half.) Dams also keep sediments from flowing downstream. This has lead to coastal beaches losing sand and to beach erosion.

Checking out the internet this week, I found some news and new science on dams and what they do to our environment.

Fewer Dams in the U.S., But Just a Few Fewer

This past year, 2020, in the United States 69 dams were removed from rivers and streams, with most of the removals occurring in Ohio, where eleven dams were removed, and New York and Massachusetts, with each of those states removing six dams. In total, across the entire U.S., 624 miles of upstream river were reconnected by dam removal. Brian Graber, senior director of river restoration for American Rivers, had this to say about the removal of the dams:

While this past year was full of challenges, restoring vibrant, free-flowing rivers has been a source of strength and progress for communities nationwide. Local partners, engineers and construction crews worked under extraordinary circumstances to complete these projects, delivering a wide range of benefits to their rivers and communities.

While Graber and other environmentalists are applauding the removal of the dams, there are still around 84,000 dams in the U.S. If we continued to remove dams at last year’s pace, we would remove the last U.S. dam in the year 3238.

But there might be more than just ecological reasons to step up the pace of dam removal. Most of the dams in the U.S. were built decades ago, back when folks in this country were big on the idea of building just about anything: skyscrapers, interstate highways, you name it. As the dams have grown old, they have become fragile and possibly prone to collapse.

The American Society of Civil Engineers gave almost every dam in our country a grade of D in a 2017 safety report. Earlier this year, straining under heavy rains, two dams in Michigan collapsed. The extreme weather that lead to the dams falling will probably become more frequent in the coming decades due to climate change, making the engineers’ report even more timely.

Small Dams in Brazil

In our imaginations we tend to think of everything east of Sao Paulo and Rio as an expanse of rainforest. But there are other ecoregions in Brazil, including the vast savanna known as the Cerrado (which is Portuguese for “thick”).

One of the most biodiverse areas on the planet, Brazil’s Cerrado is home to five percent of the earth’s plants and animals. Of Brazil’s 12 major hydrological regions, six begin the the Cerrado. The Cerrado encompasses the largest wetland in the world, the Pantanal.

There are smaller wetlands in the Cerrado, called veredas, that play an important part in the overall ecology of the region. These wetlands are composed of hydromorphic soils, which can hold a lot of water. During the yearly drought—five months of zero or next to zero precipitation—the veradas serve as natural reservoirs, slowly releasing water. Needless to say, the plants and animals native to the Cerrado are adapted to this hydrological cycle.

The expansion of agriculture in Brazil includes the Cerrado, and that expansion has only accelerated in recent years. To impound water for their cattle, farmers build dams, which are usually small and create ponds and lakes that are less than three quarters of an acre in size. Because they are naturally disposed to retain water, farmers build the dams on the veradas.

Despite their small size, these dams and ponds affect the environment of the Cerrrado. A group of scientists from a number of Brazilian universities and whose research was published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. found that the numbers of dragonflies, damselflies, and other aquatic related insects are reduced in areas where these dams have been constructed .

“Oh well, it’s just a few bugs,” I can imagine more than a few of you thinking. But I can tell you that the bugs are important. As part of my volunteer environmental work, I’ve surveyed streams for damselflies and dragonflies. These insects are one of the best ways, maybe THE best way, of assessing the biological health of a stream or wetland. Fewer dragonflies, fewer toads. Fewer damselflies, fewer birds, turtles, and foxes. You get the picture.

To ameliorate the situation, the scientists recommend that cattle ranchers rely on water tanks for their cattle instead of damming up the veradas. I would suggest that we all give up eating beef and leave the veradas alone, but that’s just me.

And When It Comes to Dams and Crayfish, It’s Complicated

Ecologists and conservationists usually see dams in one way. They are not good. Yet some scientists are finding benefits, albeit problematic benefits, from dams when it comes to crayfish conservation.

In studying the effects that dams have on aquatic organisms, crayfish have been largely overlooked. As with other river creatures, dams reduce crayfish habitat, fragment their environments and populations, and inhibit crayfish ability to recolonize habitats that may exist upstream.

European rives have been plagued by invasive crayfish from North America. Invasive species are bad enough, but the American crayfish carry a pathogen Aphanomyces astaci. European crayfish usually die within a few weeks of infections from this bacterium that was introduced to Europe in he 19th century.

The invasive crayfish are more adapted to living in still waters; so they are more suited to live in the lakes behind the dams and have an easier time mating in these environments. European crayfish are adapted to living in rivers that will get surging flows from time to time. Dams, for the most part, eliminate theses surges.

So European dams are bad for the native populations of crayfish, yet two scientists from the United States, reviewing scientific literature on dams and their effects on ecology, found that dams can help native crayfish in Europe. Zanethea C Barnett and Susan B. Adams point out that, while dams are problematic for native European crayfish, they also inhibit invasive crayfish from traveling through a stream, keeping native populations safe. In some cases, some small dams or other barriers have been built fo that very purpose. Barnett and Adams published their findings in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

Conservationists and ecologists are always facing difficult choices, but this is a particularly thorny problem. Dams are bad for native crayfish, yet they can help them. What to do? The scientists propose a sort of middle ground solution. They suggest allowing for surges downstream from dams. The nonnative crayfish don’t like this, and there is evidence that surges reduce the numbers of the invasive crayfish.

More News

More Signs That the Eastern Monarch Butterfly Is Headed Toward Extinction

You would think, as the monarch butterfly is one of the most beloved creatures that visit our backyards and parks, that folks would be up in arms to do something about the decline of this beautiful insect. The latest yearly count of monarchs overwintering in central Mexico showed a decline of 26 percent from last year.

The butterflies occupied 5.2 acres of their winter habitat. Scientists estimate that, to stay out of a population spiral of extinction, the minimum habitat threshold for the monarchs is 15 acres. The population of eastern monarchs has declined by more than 80 percent over the past two decades. (Center For Biological Diversity)

Spotted Owl Forest Habitat Regenerates After Fire Without Seedlings Planting

When large-scale fires strike in the Pacific Northwest, where the Northern Spotted Owls live, forest managers routinely allow for large post-fire logging, and the application of herbicide, and the planting of conifer seedlings, the thinking being that these forests would not quickly regenerate otherwise.

Researchers Chad T. Hanson and Tonya Y. Chi found otherwise, that the trees regenerated well on their own without human intervention. (Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution)

Great lessons. Pleasant read.