California and drought: consequences for people and the environment

The trials of severe drought on California's population and environment

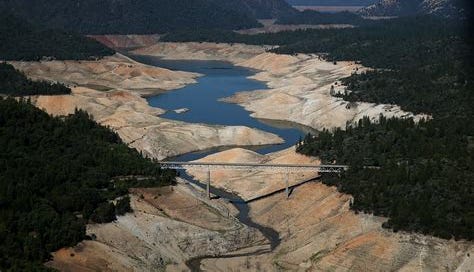

Drought has been ongoing in California for years and years. According to Drought.gov, the Golden State was in drought from December 27, 2011, till March 5th, 2019, over seven years. Other sources suggest that the drought has persisted longer. For 2021, state officials recorded the second driest year on record. And if you look at this map of present conditions in California, you’ll see that the entire state is in some form of drought, from mild to severe.

Droughts and longstanding droughts have been part of California’s history and prehistory. Using information from tree rings, scientists have been able to go back as far as the seventeenth century and found that California experienced periods of drought from 1650 to 1690, 1750 to 1790, and for 100 years after the Gold Rush, from 1850 to 1950. Other scientists have found evidence of drought going back even further in time. Our current drought is exacerbated by global heating and may be the worst that has hit California in 1,200 years.

The consequences of severe, long-term drought

A fairly recent coinage is “ecological drought,” referring to drought so severe and longstanding that ecosystems are stressed, changed, or wind up completely collapsing. Investigating if and to what extent California might be in the midst of such a dry spell, a team of researchers monitored populations of 423 species of plants, insects birds, reptiles, and mammals in Carrizo Plain National Monument, a portion of California’s Central Valley that miraculously escaped development. They conducted their monitoring from 2012 to 2015.

Counterintuitively, most of the more common species suffered, while rare species, some ants, beetles, reptiles and birds, wound up thriving. The drought driven crash of one species, for example the giant kangaroo rat, left open niches that other similar species could fill in and thrive. In the long run, creatures with slower population growth rate fared more poorly that species with higher growth rates. The carnivores—coyotes, hawks, badgers, foxes, etc.—suffered the most, with declines in all of their populations.

In another study, the scientists concentrated on drought’s effects on chaparral. Once again, there were winners and losers. shrub oaks suffered little, the same can be said of members of the sumac family: laurel sumac and sugarbush. The plants to experience the greatest mortality were what might be considered signature species of chaparral: ceanothus and manzanita. Perhaps the difference in adapting to drought could be because the sumacs are also in the coastal sage scrub plant community, which is adapted to having less precipitation and more exposure to direct sun

The scientists also found that the die-off of chaparral from drought opened up the landscape to nonnative invasive grasses, a phenomenon called type conversion. This change-out to a nonnative landscape could be exacerbated by fire, which might occur more often because of drought.

Strategies for California’s human population during this drought

California has a huge population. Data from last U.S. Census indicates that the Golden State has over 39 million people. Besides drinking and bathing, all those people wash their cars, water their lawns, and clean their homes.

Particularly striking, southern California is desert or semidesert. Coastal San Diego averages in non-drought years about nine or ten inches of rain a year. About 50 percent of our water is brought in from the Colorado River, and 30 percent from northern California. What is to be done during a drought in a place that doesn’t have that much water in the first place?

A California-based academic, Elizabeth Keavney, looked at a number of technologies and strategies to mitigate the drought’s effects on people in California, including using tugboats to haul polar icebergs to the California coast to harvest their melting ice. Looking at costs and feasibilities, she concluded that wastewater recycling, “is the most feasible method to mitigate future droughts in California.” Her study was published this month in the journal Applied Water Science.

Keavney looked at the costs of desalination, stormwater capture, water conservation, tugging icebergs, and wastewater recycling. She also considered practical aspects of each strategy. She disfavors desalination because its costs remain above that of recycling wastewater. Grabbing icebergs and pulling them through the ocean is untried, so she doesn’t give it much consideration.

Stormwater capture is basically doing what a rain barrel does but on a grand scale, harvesting rainwater from rooftops, roadways, and parking lots. Keavney judges this strategy as being impractical. Oil spilling from cars and other pollutants render stormwater too polluted to treat for human consumption. (The obvious next question: is the water then too polluted to allow it to flow into streams and lakes?)

Keavney does a fine job of giving an overview of the current state legislation that offers carrots and sticks to California residents to use less water, including recent legislation intended to replenish California’s strained aquifers. She fails, however, to adequately judge Californians’ acceptance of wastewater reuse. She says that public officials need to sell the public on the idea to overcome the “yuck” factor. When San Diego was first proposing reuse in the 1980s, the resistance to the idea was pretty fierce. (I was one of the folks in opposition.) Now, there is hardly a voice raised opposing the reuse of our water. This includes indirect potable reuse, which is taking effluent—including sewage—filtering and purifying it to meet drinking standards, and piping it to a reservoir that contains water from other sources. The reservoir water is then treated for drinking and piped to homes and businesses.

Also, I believe that Keavney doesn’t adequately consider conservation. It is the cheapest method possible. Average water use for San Diegans is 83 gallons a day, one reason being is that we water our lawns. San Franciscan, who generally don’t have lawns, use about 40 gallons a day. A drive to change our lawns to xeriscape could help a lot.

But another reason conservation could work is that California has people who use A LOT of water. In 2015, I wrote about one homeowner in Rancho Santa Fe, a tony part of San Diego County, who uses 38,000 gallons of water a day. This individual lives in a large home, on a nice spread, but he is not alone. His neighbors probably use thousands of gallons a day as well. And there are other tony places throughout California with individuals using thousands and thousand of gallons of water. There is a lot of room for these folks to cut down and help out their neighbors.

For more environmental science & news follow me on Twitter @EcoScripsit.