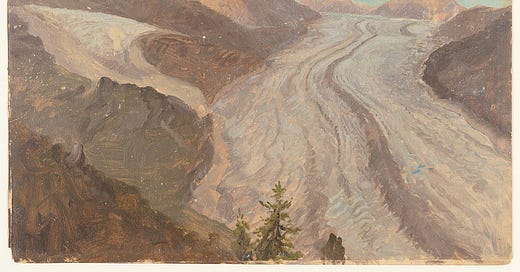

2025: The International Year of Glaciers' Preservation

Glaciers are disappearing more and more quickly

A big welcome to all the new subscribers, and hello to all the folks who have been with The Green Dispatch for a while.

Prompted by the government of Tajikistan, a mountainous country containing a great number of glaciers, the United Nations declared 2025 the International Year of Glaciers' Preservation. The international assembly also proclaimed March 21st of each year to be World Day for Glaciers. In so doing, the UN hopes to spotlight the importance of glaciers in the climate system and their roles in hydrology and ecology, as well as the benefits they provide us humans.

Glaciers have been melting for decades, as the planet warms. According to a report from the World Glacier Monitoring Service, an agency working under the auspices of UNESCO and other international organizations, global glacier loss has accelerated since the 1960s, with eight of the ten years of greatest loss recorded after 2010. The authors of the report note the loss of glaciers “leaves no doubt about ongoing climate change and sustained forcing, even if a part of the observed acceleration trend is likely to be caused by positive feedback processes (e.g., surface lowering, glacier disintegration).”

Glaciers regulate downstream water temperatures, and they play a part in the hydrology of downstream rivers and lakes. When they melt, the volume of water in rivers increases. This can disturb river and riparian ecologies, and can contribute to coastal erosion. That extra water also increases sea level rise.

In some places the big melt has been more dramatic. In just the past 20 years, New Zealand has lost almost half of its glacial ice, down by 42 percent. In Pakistan, rapid melting of glaciers has resulted in more than 3000 glacial lakes left behind in the glaciers’ retreating paths. Held back by walls of rock debris and ice, the lakes are unstable and may burst without warning. This phenomenon is common enough to have been given the terminology Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs). In May of 2022, a GLOF swept away homes and roads disappeared in Hassanabad, a city in the Hunza Valley of Pakistan. The GLOF ravaged the historic Hassanabad Bridge as though it were made of a child’s blocks.

Temperatures throughout Pakistan are rising at twice the rate of the global average. Scientists estimate that one-third of the glaciers of the Hindu Kush-Himalayan region could disappear before the end of this century.

Melting at the ends of the Earth

Hundreds of Greenland’s glaciers used to terminate at the ocean; they now terminate farther inland. Scientists have found this retreat to be so dramatic that more than 1000 miles of coastland are now free of ice and exposed. Scientists were able to track the receding by using satellite imagery from 2000 to 2020. The melting glaciers have also revealed 35 islands close to Greenland’s coast.

Beneath Antarctica’s expanse of ice is a netherworld of lakes and rivers formed by meltwater and the friction between the moving glaciers and the Earth. Like oil between gears, the water acts as a lubricant, accelerating the glacial flow to the sea. Though scientists have long know about the lakes and rivers, most of the modeling they have done on the Ice Sheet fails to account for its effect on the glacial flow, according to a statement from the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership, an organization of Australia’s leading Antarctic research institutions.

Factoring in the effects of the water, the partnership concludes that most of the research on the Ice Sheet may have seriously underestimated the discharge of ice from the continent. The flow of ice could be three times as much as previously thought. Sea level rise may have been seriously underestimated, too.

People fighting back

Inspired by the UN’s declaring 2025 as the years of glaciers’ preservation, an international team of glacier scientists has formed the Glacier Stewardship Program.

Members of the program seek to work with communities and other stakeholders to develop ways to slow glacial melt on a local scale. They also seek to develop early warning technology and techniques to ensure safety from GLOFs and other hazards of melting glaciers. Microorganisms have evolved to live in and around glaciers. The team is working to create a biobank of these organisms, tens of thousands of them, to save them from extirpation.

And NPR has this remarkable story of Saul Luciano Lliuya, a Peruvian farmer who is suing RWE, an energy company and one of Germany’s largest emitters of greenhouse gases. The lawsuit aims to hold the company responsible for its part in warming the planet and melting the glacier in the mountains above Lliuya’s home and community. Due to glacial melting, the glacial lake that lies between the glacier and Huaraz, where Lliuya lives, has grown to 35 times its normal size. A GLOF from this body of water could wipe out many of the homes of Huaraz, including Lliuya’s.